Prince’s ‘The Black Album’: A Track-by-Track Guide

It’s impossible to untangle the folklore surrounding Prince’s The Black Album from the music on the mysterious disc with no name. The album was pulled a week before its Dec. 7, 1987 release at Prince’s insistence, and instantly became one of history’s great lost albums – at least until its official limited release in November 1994.

During its seven-year period in the wilderness, The Black Album became one of the most widely bootlegged albums of all time, and as late as August 2018, an original vinyl pressing sold for $27,500 on music marketplace Discogs. And the reason for all this mystique and music industry hubbub? It’s simply that Prince became convinced that his creation was “evil.”

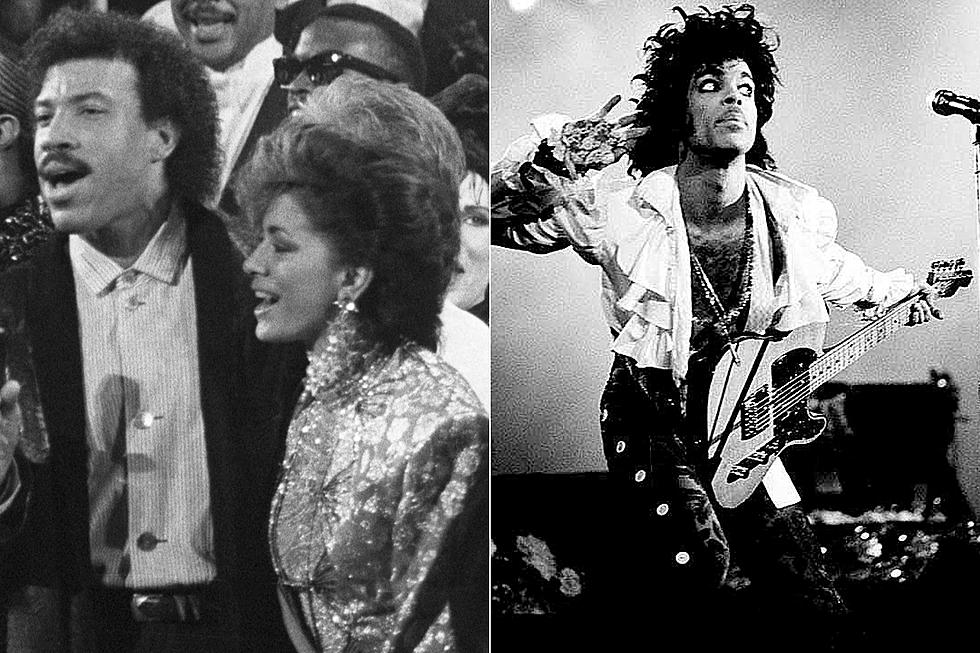

It didn’t start that way. The Black Album was planned as a counterweight to Prince’s runaway pop success, an attempt to reconnect with the African American audience he increasingly left behind in the wake of Purple Rain. To be sure, The Black Album is unlike anything Prince recorded before or since. Its raw, beat-heavy monochromatic funk is a 180-degree pivot from the colorful and eclectic pop chaos of Sign ‘o the Times, the album it was meant to follow. And only one song from the project, the soulful sexual hymn “When 2 R in Love,” made it onto the track list of Lovesexy, the album released in The Black Album’s stead.

According to a website devoted to the legendary disc, Prince went to the now-shuttered Rupert’s Nightclub in Golden Valley, Minn. on Dec. 1, 1987, where he asked the DJ to play cuts from the as-yet-unreleased album. Later that evening he met poet, singer and songwriter Ingrid Chavez, who later starred in Prince’s 1990 film Graffiti Bridge. The two went back to Prince’s Paisley Park studio and talked late into the night, where Prince, reportedly under the influence of ecstasy, experienced terrifying hallucinations and realized that it would be irresponsible to release such a dark, negative and evil album. Prince may have been alluding to this event in the 1988 tour program for his subsequent Lovesexy tour:

“Tis nobody funkier—let the Black Album fly. Spooky Electric was talking, Camille started 2 cry. Tricked. A fool he had been. In the lowest utmostest. He had allowed the dark side of him 2 create something evil.”

By this reading, Camille, Prince’s high-pitched female alter-ego, who was to be the focus of a self-titled album that Prince abandoned while recording Sign O' the Times, had his/her revenge. Under Camille’s malign influence, a demonic entity named Spooky Electric materialized and Prince channeled the entity to create the album. In any event, Prince later claimed he became concerned that The Black Album might become the last thing he recorded before he died. He didn’t want his legacy to be marred by such blackness.

With such a supremely occult and creepy build up like that, can the album live up to its reputation? The short answer is no. What music could?

Opening funk jam “Le Grind” is all about le groove. Recorded for drummer and vocalist Sheila E.’s birthday party in 1986, the track name-checks “The Funk Bible,” an early and abandoned title for the album. Eric Leeds’ saxophone and Atlanta Bliss’ trumpet shape-shift and slide in sideways to execute blaring switchbacks like crosstown traffic. Meanwhile Prince’s guttural, comically sinister synthesizer slips through the beats like a lumbering mastodon.

The heavy metal funk gives way to the organized dance floor chaos of “Cindy C.” Inspired by an incident where supermodel Cindy Crawford danced with Prince without realizing it was him, the tune plays like a satire of Prince’s image. Singing in a scratchy falsetto amid a dissonant spiral of horns, Prince portrays an arrogant-yet-failed player who can’t get anywhere with the object of his lust. It’s Prince’s self-reflexive parody of Prince.

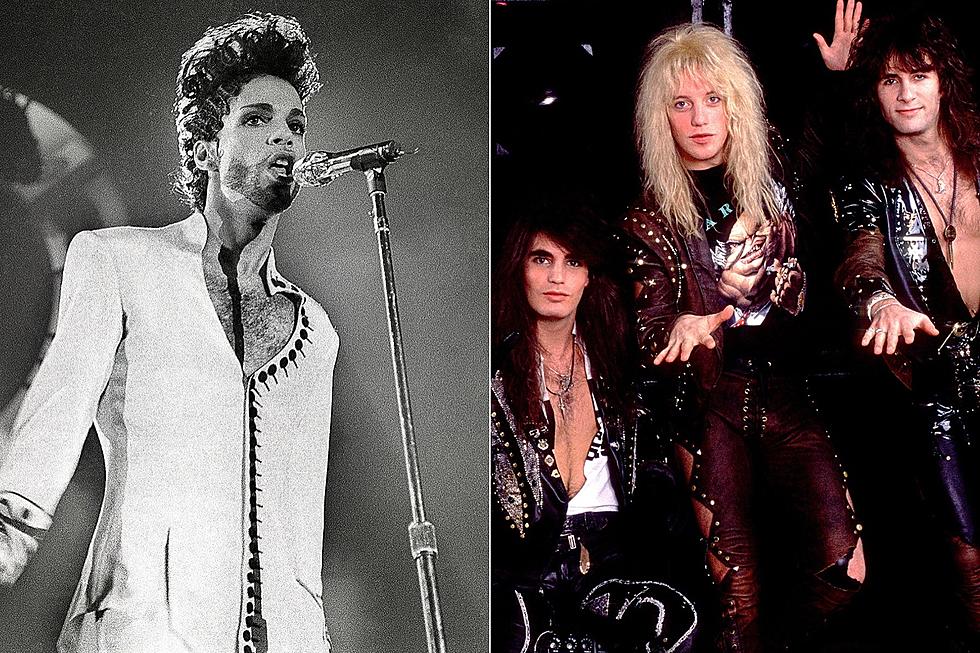

A shotgun blast of percussion kicks off “Dead On It,” Prince’s critique of all rap, circa 1987, saying that rappers are tone deaf and can’t sing. Despite Prince’s slicing coils of razor guitar, this is one of the few cringe-worthy cuts on the album. Hit hip-hop songs in 1987 included groundbreaking jams by Public Enemy, LL Cool J and Eric B & Rakim, and Prince’s anti-rap rant comes off like the mutterings of an uninformed crabby old man. Within a few years, however, Prince had changed his mind on hip-hop, bringing rapper Anthony "Tony M." Mosley into the New Power Generation.

“When 2 R in Love” is the outlier on the album, which may be why it alone was retained for Lovesexy. It’s the only cut concerned with the flux and tension between spiritual and carnal love, a theme that runs through much of Prince’s best music but which is notably absent on the rest of The Black Album. The record's prettiest melody is carried by Prince’s whispered pillow talk and soulful croon over clacking electronic beats and jazzy cascading piano.

Writing for The Quietus in 2016, Simon Price calls the following track, “Bob George,” “[T]he most fucked up thing in Prince's entire catalog.” He may have a point. Over brutal impersonal beats punctuated by sawing squalls of atonal guitar, Prince plays toxic masculinity personified. With a low electronically altered voice, he portrays a character abusing his girlfriend, who also finds time to badmouth Prince as “that skinny motherfucker with the high voice.” The chilling vignette ends with violence and gunfire. If Spooky Electric is to be found anywhere on this album, it’s here.

With squirrelly corkscrewing synths and a burst of maniacal laughter, “Supercalifragifunkysexy” lightens the mood with a mash up of George Clinton’s P-Funk and Mary Poppins. Amid squeals of pleasure and wonky roller-rink organ, multiple harmonized voices sing about blood rushing to the head, a need to dance and a lust for sex. The playful groove seems to be a lampoon of people who take ecstasy, and it raises the possibility that Prince is excoriating his own use of the drug.

On his YouTube channel, Prince’s Friend says “2 Nigs United 4 West Compton” sounds “like something recorded for [Prince’s jazz fusion group] Madhouse by the Lovesexy band." The uplifting old-school groove finds space for slicing horns, jangling guitar, squelchy synths and cantering bass. It’s the jazziest cut on the album.

A co-write with Eric Leeds, “Rockhard in a Funky Place,” is the only song on the album not composed entirely by Prince. The mid-tempo groove, interspersed with spiraling horns and shards of psychedelic guitar, is something of a smutty joke, the tale of a lad who goes to a whorehouse with an erection but is unable to perform. The track fades out, but Prince’s voice returns amid a wave of squalling noise to deliver the question that ends the album: “What kind of fuck ending was that?”

Even though he had The Black Album shelved, Prince performed “Bob George,” along with “Supercalifragifunkysexy” and "When 2 R in Love" on the Lovesexy tour, during the first part of the show which focused on his darker music. The project may not have been conjured up under the demonic directive that has passed into legend, but The Black Album still flirts with darkness. The funk, drugs, sex and conquest encountered in “Supercalifragifunkysexy,” “Cindy C” and “Rockhard in a Funky Place” seem energetic but not much fun. The tunes are depictions of desperation masked as carnality. It’s possible The Black Album was conceived not in some dark ritual but during a period of self-reflection for Prince. Perhaps he needed to exorcise his doubts and dark thoughts under the guise of black humor before he could move on. If so, The Black Album is a riveting document of an artist fearlessly facing down his demons – whether real or metaphorical.

Prince Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Prince