Mo Ostin Explains Warner Bros. Side of the ‘Black Album’ Saga

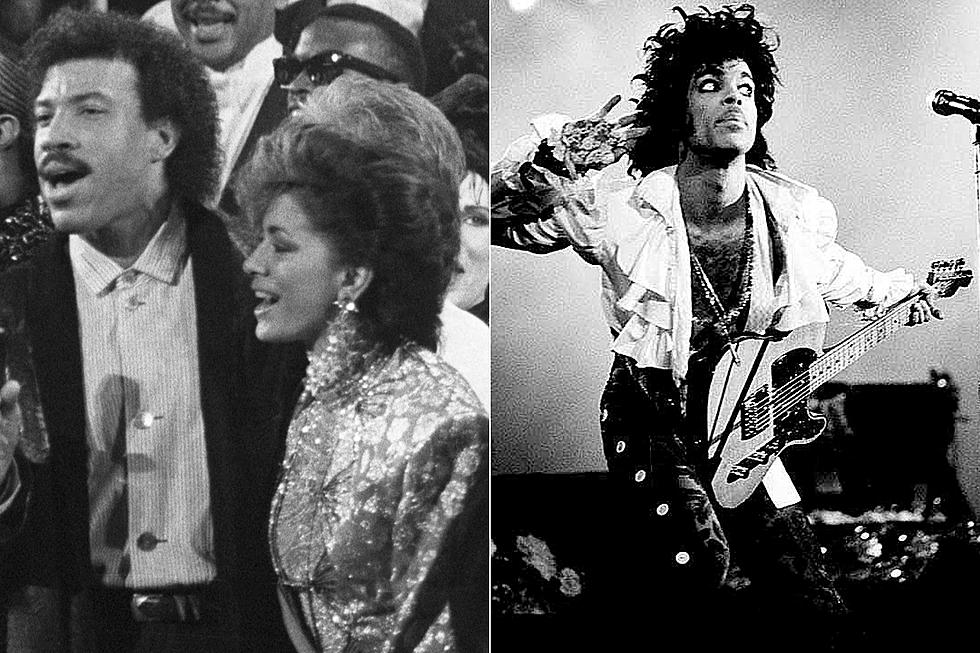

It started as a celebration. "Le Grind," and several others that made their way onto Prince's The Black Album, were initially recorded for a birthday party he was hosting for Sheila E. So it's that much more curious that he eventually dubbed these birthday songs too dark for release.

The Black Album was so-called not just because of its dark content, but its plain black cover, with no title, no credit and no liner notes. This was all before he began his campaign to split from Warner Bros., alleging a contract tantamount to slave labor and changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol. But still, he had planned to go incognito, and added the opening spoken word intro "So you found me, good, I'm glad" to begin his presentation to fans on "Le Grind."

But it wasn't to go public until 1994. According to Mo Ostin, who led Warner Bros. Records, to which Prince was signed, the original album, and its eventual destruction, were both at the insistence of the artist himself, and both against the labels wishes.

During promotion for his 1987 album Sign O’ the Times, the prolific artist was already hot on a new idea, and wanted it released right away. The label had concerns about interrupting the marketing cycle for one album to release another nine months later.

"While we were [promoting] the record, he went to a bunch of discos -- he would always do that -- and he wouldn’t hear his records being played, and he was very upset," Ostin told Billboard. So he decided he wanted to make a record that was [more dancefloor-friendly], and he made The Black Album.

"He insisted that we release it at the same time we were working Sign O’ the Times, and it would have disrupted our entire marketing plan," Ostin continued. "We tried to talk him out of it: 'You can't put a record out to interfere with the existing record.' But he insisted, and we again went along with him."

Ostin, who presided over Warner Bros. throughout most of Prince's time on the label, leaving two years before Prince's well-publicized 1996 split, said the incident wasn't unusual. "It was always a battle, there was always some problem about releases. But in most cases he prevailed," he said.

It seemed the only one who could change Prince's mind was ... Prince. Just a week before the album's release, he had a change of heart. "I was very angry a lot of the time back then," he said in a 1990 interview, "and that was reflected in that album. I suddenly realized that we can die at any moment, and we'd be judged by the last thing we left behind. I didn't want that angry, bitter thing to be the last thing."

After all, it included songs like Songs like "Bob George," about a critic who had once championed his music but became less supportive, "Cindy C," about a less-than flattering dance floor interaction with Cindy Crawford and "Dead On It," in which he purportedly disses the whole genre of rap. Anger abounded.

Prince never fully explained why he scrapped the album. What is known is that, on Dec. 1, 1987, he met Ingrid Chavez at a Minneapolis club. Later that night, at Paisley Park, the two launched into a lengthy conversation about life, faith and love.

"A lot of things happened, all in a few hours," he said in Prince: Inside the Music and the Masks, where he claimed he'd been visited by God. "And when I talk about God, I don't mean some dude in a cape and beard coming down to Earth. To me, he's in everything, if you look at it that way."

This vision may have been influenced by drugs. Two members of his entourage, who were at the club, said that he had taken ecstasy, and his engineer Susan Rogers, who was at Paisley Park, said, "I'm certain he was high. His pupils were really dilated. He looked like he was tripping."

But whatever the cause, he nonetheless insisted the album be pulled at the last minute — after half a million copies had already been pressed. Prince went to Ostin and pleaded with him to hold off. "We told him we had spent a lot of money getting this thing ready for market, and he said, 'Look, I want you to take all those albums and destroy them and I'll pay for whatever cost you guys incurred in manufacturing,'" Ostin said. "And he actually paid us out of his royalties."

But the company actually held back some copies "just to have them." Ostin guesses there were maybe a hundred that remained, and just one of them eventually got him into some hot water. At a Jamaican retreat a few years later with the newly merged Warner and Time Inc, he met writer and editor Dick Stolley, who asked for a copy of The Black Album, promising to keep it under wraps.

"Finally, I said, 'Well, we can trust Stolley, he's a guy who has an incredible reputation and a lot of integrity. Let's let him have it,'" Ostin recalled. But soon after, Prince showed up at his office with Kim Basinger, giving Ostin and Lenny Waronker, president of Warner Bros., a listen to the Scandalous Sex Suite EP the two had made.

"Prince got up from where he was sitting, went up to Lenny's desk -- and there on his desk was the copy of The Black Album that we were going to send to Stolley. He looked at it, picked it up, put it back on the desk and made no comment. I came up with whatever excuse I could make, I told him that this was somebody we could trust and might be valuable in getting exposure for Prince, maybe a cover of Time magazine, who knows? It turned out to be less of an issue than we thought it might, but our hearts dropped when we saw him pick up that album."

More From Ultimate Prince