Why Warner Bros. Finally Pulled the Plug on Prince’s Paisley Park Records

Paisley Park Records had released 23 albums when Warner Bros. ended things on Feb. 1, 1994. That included six multi-platinum projects, though none of them was issued by an artist not named Prince.

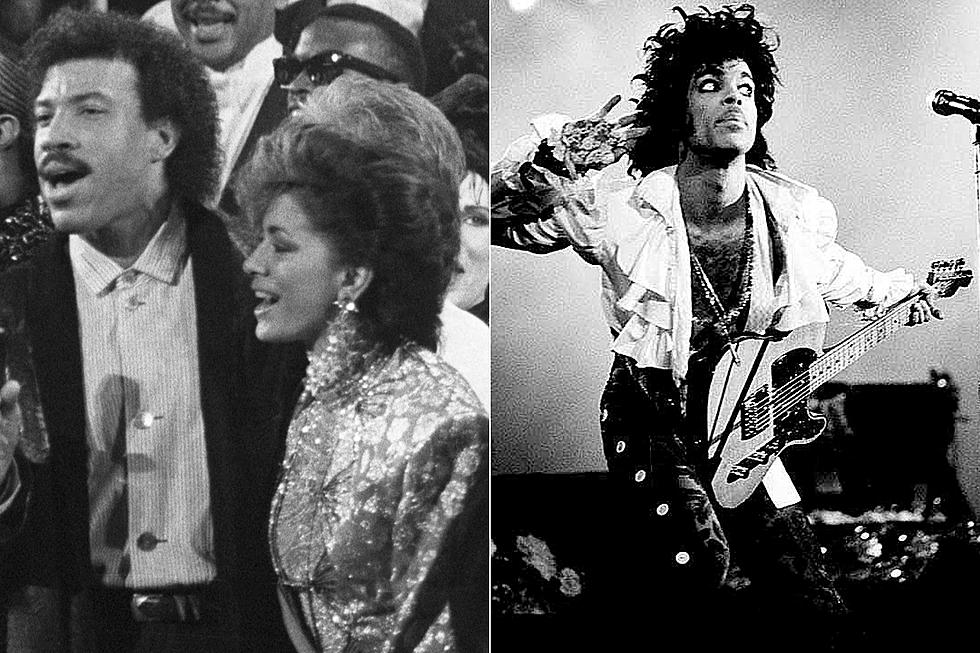

An insular visionary, Prince simply couldn't turn himself into the musical auteur Warner Bros. was expecting when they agreed to help him launch his own imprint. He was also responsible for almost all of the label's Top 20 hits between 1985-94, save for exceptions like Sheila E's "A Love Bizarre," the Time's "Jerk Out" and Tevin Campbell's "Round and Round."

"Prince was a great producer, and Warner was interested in doing a joint venture with him," Paisley Park Records president Alan Leeds told Billboard in 2016. "He'd already proven himself as a producer. [The Bangles'] 'Manic Monday' was a huge hit. He had a behind-the-scenes role on Stevie Nicks' 'Stand Back' that the industry was aware of, even if it was uncredited. And, of course, the Time records and first Sheila E. record were very successful for Warner Bros. So, they felt pretty confident, like, 'This is a guy we could bankroll a label on and see what happens.' And unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, [success] never really did happen."

Instead, Prince ran the label with the same idiosyncratic approach he took with his own career. Paisley Park Records began as a vanity nameplate, and basically ended up in the exact same place. There were plenty of bad business deals, questionable signings and head-scratching decisions along the way.

Prince's original agreement called for him to deliver masters to Warner Bros., who would make, distribute and promote the albums. The deal was revised in 1992 when Prince re-negotiated his contract. Thereafter, the two entities operated as equal partners, sharing profits and investments.

"They said, 'We've supported you and we've never ever said no to something you wanted to do. So, when are you going to come with something that will help subsidize that?'" Leeds told City Pages in 2001. "My feeling was, that was a generous attitude to have."

Watch Prince Perform 'Paisley Park'

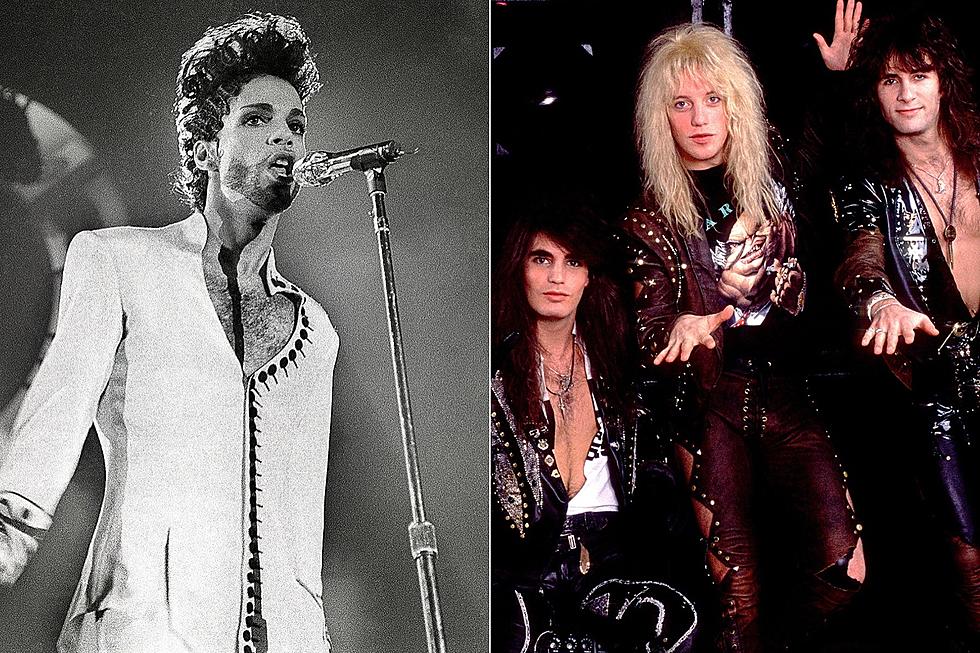

Things actually kicked off with a bang, as Prince released his second chart-topping album, 1985's Around the World in a Day. Unfortunately, Paisley Park Records never reached those lofty heights again. As Prince's personal commercial engine began to slow, there was additional pressure to make good on the label's outlay in Paisley Park Records. The partnership began to quickly fray.

"Paisley Park was not really a priority with Warner Bros.; I don't know if their commitment was so real," studio engineer David Rivkin later countered. "I believe it was kind of a carrot they held in front of him to keep him on Warner Bros."

Still, it's clear now that Prince spent most of these years working on pet projects. Paisley Park Records ended up releasing a series of albums from his latest proteges (including Jill Jones, Carmen Electra and Ingrid Chavez), a fraternity of offshoot groups (Mazarati, Madhouse, the Family) or old-school figures looking for an elusive comeback (George Clinton, Missing Persons' Dale Bozzio, Mavis Staples). Worse, there was a sometimes-uncomfortable sameness to it all.

"Invariably, no matter who the artist was, he tried to force them into his thing," Leeds rightly noted. "He never displayed the ability to park his own agenda. When he produced Patti LaBelle, it sounded like a Prince record. It became his vision, not the artist's."

Even the smart moves ended up in a stumble: Prince tried to sign Bonnie Raitt, but she went with Capitol instead – then earned an Album of the Year Grammy for the resulting Nick of Time.

Paisley Park Records was an even bigger mess internally. Cavallo, Ruffalo and Fargnoli, Prince's management team at the time, began signing artists – sometimes without any involvement from Prince. Warner Bros. attempted to recoup some of their investment by having major artists record at Paisley Park, but Prince was often notably absent. In fact, Prince basically abdicated any label responsibilities, beyond overseeing his own projects.

"I was under the assumption that it was a joint effort," Prince told the Los Angeles Times in 1996. "All we do as artists is make the music. I didn't think I'd have to be marketing the records, or taking them to the radio station. If Michael Jordan had to rely on someone to help him dunk, then there would be trouble."

Listen to Sheila E. Perform 'A Love Bizarre'

Stunned that Prince "failed to disguise his lack of interest" in these outside acts, Leeds resigned his post as Paisley Park president in 1992. "Prince wasn't taking the responsibility to produce competitive records and turn the label around," Leeds says in Prince: Life and Times. "I ended up spending several very frustrating years trying to get Warners and the industry to take Paisley Park Records seriously when they simply didn't want to be taken seriously."

Cavallo, Ruffalo and Fargnoli were subsequently fired; a resulting lawsuit then revealed headline-grabbing tales of mismanagement. Later, Prince decided to change his name to an unpronounceable symbol as he took his fight with Warner Bros. public. Another string of flops found their way to record-store shelves. The label apparently resorted to paying Prince to stay away as they tried to cash in on a greatest-hits package.

Fed up, Warner Bros. finally pulled the plug in 1994, ending a distribution deal that effectively closed the imprint. Leeds said their argument was that "a succession of 'girlfriend' records and Prince's generosity towards legacy artists past their prime weren't representative of a real label."

Prince retained the masters of all of the artists, and quickly launched a new independent label called NPG Records. But everything then in process at Paisley Park Records ground to a sudden halt. Rosie Gaines had a completed album titled Concrete Jungle set for release in March 1994; a single, "My Tender Heart," was scheduled, too. Both were withdrawn. Two other signees, Belize and Tyler Collins, were left without contracts when the imprint folded; Belize also had a record shelved.

"Let's face it: Warner Bros. was motivated to invest in a Prince record label simply because of his proven ability to conceptualize a project and then write and produce hit songs. He had done it for the Time, Vanity 6, Sheila E. and even the Bangles – albeit on another label. Warners wanted more of that," Leeds said in 2007. "What they got was a series of projects which had artistic credibility but lacked mainstream appeal. That doesn’t discredit the viability of those artists. This business has always been full of fascinating, gifted artists who, for one reason or another, never got that one magic song that was capable of racing up the charts. Still, there’s no doubt that several Paisley Park Records could have benefited from more creative input from Prince."

Meanwhile, a lasting image emerged as the full scope of this misstep became clear: During their 1992 contract renegotiation, Warner Bros. agreed to give Prince an office suite in Century City, complete with 12 staff members, to operate business affairs for Paisley Park Records. When the imprint was shuttered some two years later, Prince had still never set foot in the building.

What Happened to the Artists of Paisley Park Records?

More From Ultimate Prince