Maybe We Should Just Leave Prince’s Vault Closed

I'm the biggest Prince fan any of my friends know, so my phone and Facebook account have been blowing up with condolences all day. One of my sisters sweetly tried to cheer me up by pointing out that his famous vault, which supposedly contains hundreds if not thousands of unreleased songs, would finally be opened.

And yes, that inevitable, endless parade of posthumous releases is indeed probably on the way. But is that a good thing?

If you're a fan of any artist who's passed away and left unheard music behind – and if you're a reader of this classic rock-focused site, that's probably true – you've undoubtedly watched as seemingly each and every one of those recordings regardless of quality or historical importance has found its way to the public, and depending on your level of fandom, possibly to your personal music collection.

If they try to do that with Prince, it might take a mighty long time. A 2015 investigation by the Guardian suggests there could be enough music at Paisley Park to release a new album every year until "sometime in the 22nd century" – that's 2101, at least. Composer Brent Fischer, who has added orchestration to Prince's music since 1985, estimates that 70 percent of the music they've made together has yet to be unveiled.

Like any hardcore fan of Prince, I've daydreamed about being allowed to visit or even curate the contents of that vault. I even own a bunch of bootlegs containing dozens of tracks that have mysteriously leaked from the Purple One's famous all-hours recording sessions.

But suddenly "posthumous" is the only kind of Prince record we're going to get from now on. (Which, by the way, is a damn shame because his latest album, January's HITnRUN Vol. 2, was his best in at least two decades.) And that brings to mind a trend that's been hard to ignore: Without naming names, it's hard to deny that whoever is in control of the estates of some of our favorite dead rock stars or defunct bands probably should have stopped excavating those particular vaults at some point in the past -- if we're speaking from a purely creative point of view.

But they won't. Every holiday season, every Record Store Day, every major release date anniversary provides a new reason to dust off rare studio recordings, demo tapes or live performances to create a new album or an enhanced version of a old one. The financial motives are obvious, but at some point you have to realize or admit that what's being released isn't something the artist ever considered sharing with the world in this manner.

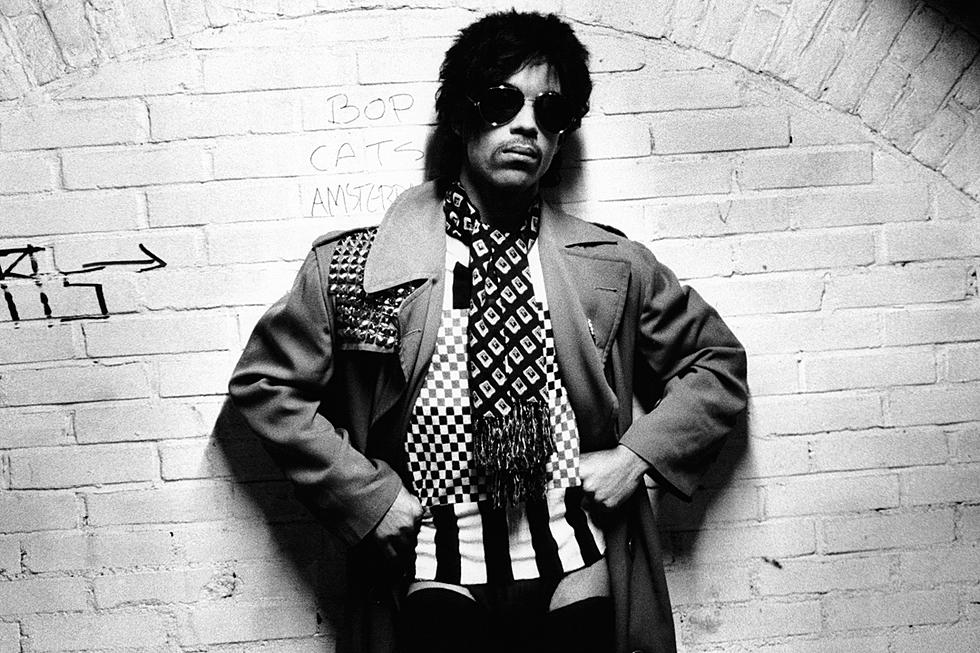

This is an especially big concern when it comes to Prince, perhaps the most private and self-contained music-making superstar ever, famous for his multi-instrumental skills as well as for forbidding interviewers to record him in conversation. Most of his records contain a credit line such as "produced, arranged, composed and performed by Prince," and it was obvious that he put much care into the sequencing, packaging and presentation of each of his 39 studio albums. Even the cover of Chaos and Disorder, an (appealingly) tossed-off collection he released in 1996 primarily to free himself from a contentious relationship with his record label, is loaded with symbolism that clearly displayed how he felt about the world around him at that time.

More importantly, in this age of social media and unprecedented artist access, Prince managed to maintain his mystique. Even as the quality of his recorded output slid from non-stop brilliance to less dependable genius over the years, every few years he'd pop up on the mainstream radar to remind us that he was a once-in-a-lifetime talent -- proving he's the only one who should ever be allowed to perform at the Super Bowl, or blowing Tom Petty and other rock legends off the stage at the at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The name "Prince" still means something very special and distinct.

No matter how well-informed or well-intentioned the person who assembled it is, a posthumous release can never fully replicate and present the full vision of the original artist. That doesn't mean these projects can't reveal amazing, completely worthwhile new music, but an undeniable dilution of some degree kicks in the moment that artist leaves the process, and that means we could lose Prince's mystique.

Did he leave specific notes about how to put together the "real" Crystal Ball, the three-disc set that ultimately got pared down to his 1987 double-album masterpiece Sign 'O' the Times? Then great, let's hear it. Undoubtedly, former collaborators such as Susan Rogers, his longtime sound engineer, could assemble plenty of great, cohesive albums that reveal new perspectives on his genius and working methods.

But eventually, unless whoever is in charge of his affairs demonstrates a level of restraint that seems to have eluded most people in that position, we're going to move past the point where Prince's music is released for strictly creative reasons, or less cynically, into sharing music presented differently than he would have done himself.

For someone who fought so hard not only to maintain his individuality and artistic purity but also to redefine the rights of the artist – changing his name to a symbol and painting "slave" on his face in the mid-'90s, steadfastly refusing to allow his music on YouTube and so on – this would be particularly tragic.

For the past 30 years or so, I've bought every single piece of music with Prince's name on it the day it came out, and I very much doubt I could break that habit if I tried. But last Saturday, I visited my local record store long after the Record Store Day mobs had picked the bins nearly clean. What remained were multiple copies of unnecessary live albums or re-releases by some of the biggest, but also over-marketed, artists in rock history.

In the same Guardian story mentioned earlier, onetime Prince manager Alan Leeds declared that his former client "said that one day he’d just burn everything" in his vault. If, as recent history seems to suggest, moderation is something that can't be achieved with these posthumous release schedules, then the choice comes down to maintaining the purity and individuality of the amazing music Prince shared with us in his lifetime, or risking seeing that work become commonplace, even unwanted "product." And if that's true, then instead of wringing all of the magic and mystery out of yet another source, it might be best just to leave his vault doors closed forever.

Prince Magazine Ads Through the Years: 1978-2016

More From Ultimate Prince