BrownMark Talks Race and the Revolution in New Book: Exclusive

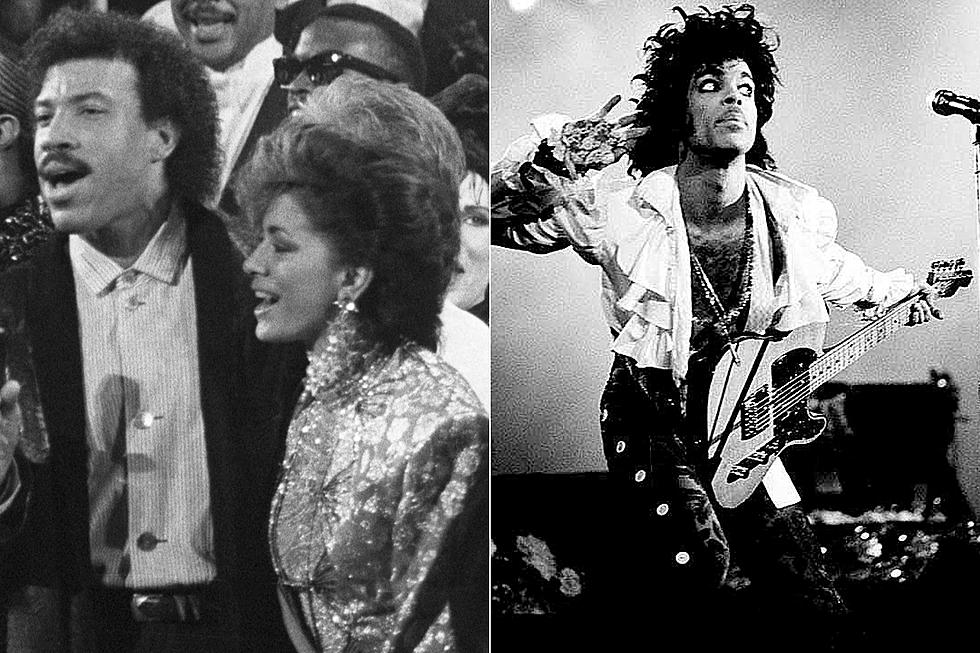

In his long-awaited new book, bassist BrownMark talks about being the only other black man in Prince's Revolution, and how the duo dealt with changing audience demographics as their fame grew.

Written with Cynthia M. Uhrich and published by University of Minnesota Press, My Life in the Purple Kingdom captures the man born Mark Brown's journey from being confined to the “Chitlin’ Circuit” of local black clubs to playing arenas with the Purple One as BrownMark. He officially joined Prince’s band in 1981, replacing bassist André Cymone, and left at the end of the Parade tour in 1986. He provides his account of noteworthy moments in Prince’s career, from getting booed opening up for the Rolling Stones in 1981 to enduring Purple Rain mania.

Brown wrote the book about 15 years ago as an act of therapy. “The lifestyle really took its toll on me,” he tells us. “It wasn’t a book to be published right away. It was just writing down to vent and let out a lot of frustration.”

Some of that frustration came from his experience as a black man in America. “It was rough,” he continues. “Part of my therapy was just having to figure out how to deal with the inequality and injustice.”

Brown writes about the racism he experienced as a child in Minneapolis and even after he had fame and money. And as the only black member of the Revolution besides Prince, who was always busy with other things, he felt like he didn’t belong. “They don’t understand the depth of my struggle,” he says. “Their humor is different. Their topic of conversation is different. … So, it was weird being the black guy in the group, especially as the music started to change.”

Brown noticed a shift in the demographics of the audience at the end of the 1999 tour. “I see all of these caucasian folks in the front rows,” Brown says. “I’m like, ‘Where’s the black people? They’re all up in the bleachers. They get the bad seats.’ … It just didn’t sit well with me. And I remember Prince was really bothered by it, too.”

According to Brown, Prince brought up the issue with promoters, who were able to achieve a more balanced turnout for the Purple Rain tour. Even as a crossover artist, he notes, Prince did not want to leave black fans behind.

“A lot of people don’t do that,” he says. “They just want to cross over and make the money. Prince wanted to cross over and unite people with his music. He was rooted in his blackness. He understood it very clearly, but he also understood that there was a game that needed to be played so that he could cross borders and genres.”

Mark Brown heard Prince before he met him. He remembers standing in an alley outside of Central High School in Minneapolis as Prince’s band, Grand Central, played a dance. About four years Prince’s junior, Brown was too young to get inside.

“They were tearing it up,” says Brown, who grew up in Minneapolis and played bass with his band, Phantasy, on the local music scene. “I always knew that [Prince] was awesome, a great musician. … I knew the girls liked him. I always heard about this little light-skinned boy with a big ‘fro and all the women loved him.”

Brown saw Prince years later at a restaurant. Prince was a rising star with a new, punk-inspired sound, and Brown was working in the kitchen.

“I proceeded to make him pancakes with a special touch of vanilla extract,” Brown writes in My Life in the Purple Kingdom. “I wanted to impress him for some reason, even though he wouldn’t even know who was cooking for him. … I remember him laughing at me because I was a bit obnoxious peeking in on him.”

A short time later, Brown was performing beside Prince in the band that would become the Revolution, one of the most famous acts in the history of popular music.

Brown has fond memories of creating with Prince. “You could always tell his mood when he walked into rehearsal,” he adds. “I used to really enjoy the jam sessions when he was in a good mood. The jams were fun. When he was in that tyrannical mood, the jams were long and boring.”

But he also doesn’t shy away from the hurtful experiences of working for Prince. There were money and credit disputes, and Brown often felt Prince was diminishing his role in the band. The most famous slight involved Prince’s No. 1 song “Kiss,” which he originally gave to Mazarati, a band Brown was developing. Prince took it back after Brown and engineer and producer David Z. Rivkin worked on the song. Brown says Prince probably looked at him like a little brother, and picked on him accordingly. But he doesn’t quite know how to explain some of Prince’s actions.

“I always wondered, ‘Dude, why are you trying to suppress me? Why, every time I move forward, you try to push me back somehow?’ … [But] we loved each other. Regardless of all the stupid stuff that went on, we developed such a close bond.” After parting ways with Prince, Brown signed with Motown. Then he took a break from the music industry, went to college, worked in the tech industry and raised his children.

Through it all, he and Prince kept in touch. “He would call me a few times a year at the oddest hours,” Brown says. “Sometimes, my kids would be up. They would answer [and say], ‘Somebody says his name is Alexander Nevermind.’ … He would keep me on the phone two or three hours just reminiscing. So, I knew he just needed a friend.”

Brown has since returned to the industry, making music with his band, the Bad Boyz of Paisley. The Atlanta resident is currently promoting his album, House Party, and single, “Empty Handed.”

Over the years, he and Prince made plans to work together again, but they never materialized. Recently, the two were rekindling their friendship, but their time was cut short when Prince died in 2016. “It was heartbreaking,” Brown says. “There was still so much more I wanted to clear the air with him about. … And I think he was at a place where he was willing to talk about it.”

Prince's Bandmates: Where Are They Now?

More From Ultimate Prince